Rising Youth Crime: Youth violence threatens the safety and well being of our society. Each day Americans wake up to news reports of fresh outbreaks of violence in schools and on our streets. A sense of desperation and fear is rising as we see that police and government leaders can't create a safe environment for our children. Although we spend over $400 billion on crime each year, our children are among the most likely in the world to be victims of senseless violence.

The Origin of Violent Behavior: Numerous factors have been shown to contribute to this violence. These can be divided into two categories: nurture: (bad parenting; acute stress in childhood; poor education; violent TV, movies, and video games; growing up in neighborhoods with gangs and violence; low socioeconomic status; and easy access to drugs, alcohol and lethal weapons) and nature: (genetic and other physiological factors) (1).

|

| Images courtesy of Dr. Daniel Amen |

Recent research indicates that these combined factors of nurture and nature can lead to specific biochemical imbalances and brain abnormalities that form the biological roots of violence. A growing body of research implicates mounting stress levels in the individual and society as a primary causal factor in social violence, especially youth and school violence (1-6).

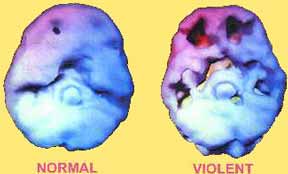

Chronic and acute stress leads to an out-of-balance neurophysiology, as evidenced by brain biochemistry (elevated levels of stress hormone, cortisol, and suppressed metabolism of the 'well-being' neurotransmitter, serotonin), and brain electrical patterns (low encephalographic coherence). These aspects of neurophysiological imbalance are the two most consistent predictors of antisocial behavior. Over time, these biochemical and electrical imbalances become physiologically 'entrenched', leading to acute and chronic brain dysfunction. USA Today and other publications have featured pictures of "normal" brains vs. "violent" brains.

These SPECT images graphically reveal the presence of "functional lesions" (areas of low-metabolic activity caused by the absence, or near absence, of neuronal firing) in the prefrontal lobes of violent children--the region of the brain that normally provides a filter against impulsive, aggressive and violent behavior.

Substance abuse such as cocaine, marijuana, and alcohol has also been shown to create these "functional lesions" in the brain.

A Solution to Violent Behavior: Based on years of research with brain biochemistry and EEG, we expect our research to show that the Transcendental Meditation® (TM®) program, produces a dramatic reversal of this "neurophysiology of violence" and of violent behavior in students and youthful offenders (7-14). This stress-reducing technique has been successfully used in schools and in criminal and drug rehabilitation settings to reduce school violence, drug and alcohol abuse, violent prison behavior, and prison recidivism among violent offenders.

Meditation Intervention: The Transcendental Meditation technique is a simple, natural, mental procedure. It allows the mind to effortlessly settle down and to experience more refined and quiet states of the thinking process. During the TM technique, one experiences restful alertness, a state of minimal mental activity and corresponding deep physiological rest (for review see 12, 15) . Since every experience leads to corresponding alterations in brain chemistry and structure, one would expect wide-ranging effects from the unified, integrated experience of the TM technique on brain activity and mental and physical behavior. Over 600 research studies on the TM program conducted over the last 40 years have documented improvements in numerous aspects of physiological and psychological function. Marked improvements have been reported, for example, in self-confidence and self-esteem, IQ, creativity, memory, cognitive flexibility, emotional stability, academic performance, and psychological maturity. More specifically, the TM technique dramatically alters two physiological correlates of violent behavior by (1) balancing the neuroendocrine system as seen in increases in serotonin metabolism, and in decreases in cortisol levels, and (2) increasing global brain coherence as measured by electroencephalographic techniques (for review, see 14, 16, 17).

Justification for Choice of Intervention: There are numerous methods currently purported to reduce stress. Although any stress-reduction technique will lead to some alteration in experience, these methods produce strikingly different results (18). Thus, the choice of methods utilized may be critical for optimal effectiveness in reversing the neurophysiological and psychological effects of stress.

Early research found marginal or insignificant results for some of the procedures once thought to decrease stress (19-21). For instance, Eisenberg et al., who conducted a meta-analysis of 26 studies that evaluated Benson's relaxation technique, progressive muscle relaxation, biofeedback, meditation (excluding TM) and other "stress management" procedures, found that the efficacy of these approaches in reducing hypertension was equivalent to that of placebo techniques (22). Comparative studies suggest that Maharishi Mahesh Yogi's Transcendental Meditation technique is the most effective, scientifically researched stress reduction program, as measured by many physiological and psychological parameters (7, 23 26). A more recent summary of 8 meta-analyses of 597 studies, comparing the TM program and other stress-reduction techniques, confirms the TM program's effectiveness (see Figure 2 in Appendix, 18).

In conclusion, comparative research studies indicate that the TM program is the most effective stress-reduction program, and thus, potentially the most capable of reversing the physiological basis of violence.

SPECT, the Latest Diagnostic Technology: This study will be the first to employ the latest and most sophisticated brain diagnostic technology -- (SPECT) -- to examine the effect of the TM technique on violent children and to document the ability of this natural and effortless procedure to effectively reverse the neurophysiological roots of violence and modify social behavior in the direction of more harmony, integration, and balance.

SPECT (single photon emission computer tomography), reveals a remarkably consistent and dramatic image of major brain dysfunction in aggressive, violent individuals. In Figure 1 below, brain metabolism of a violent individual is strikingly reduced in many areas, especially in the crucial prefrontal lobes that normally provide an effective filter against impulsive, aggressive, and violent behavior. Note that physical lesions of the brain caused by head injuries can be the cause of aggressive, violent behavior. While the subjects below have had no head trauma and have no actual lesions, SPECT graphically reveals the presence of what can be considered "functional lesions" (regions of low metabolism and hence chronic dysfunction) in the brains of violent subjects. SPECT imaging thus provides an invaluable diagnostic "window" into the dysfunctional brains of violent youth.

|

| Images courtesy of Dr. Daniel Amen |

Figure 1. SPECT imaging of normal and violent subjects. These views of the human brain illustrate the extent of blood flow (normal brain on the left, brain of violent individual on the right). Brain blood flow is directly related to the degree of neural activity and hence to brain function. Note that brains of violent individuals have greatly reduced levels of activity compared to controls. Areas of chronic dysfunction (functional lesions) appear as "holes" in the brain. Note especially in the violent case [top of image], these regions occur in the front of the brain--the region of the brain that normally provides a filter against impulsive, aggressive, and violent behavior. The lesions thus may be expected to cause significant loss of impulse control, decision making, learning ability, moral reasoning, and emotional stability.

The Transcendental Meditation program can dramatically counteract the debilitating effects of chronic stress so prevalent in our society and school systems. Research has shown its ability to reduce violence in stress-ridden inner-city schools, reduce drug and alcohol dependence and criminal behavior, and even reduce recidivism among maximum-security inmates.

Modern physiological research on the causes of violent and aggressive behavior has identified two strong neurophysiological correlates: abnormal neuroendocrine patterns and abnormal metabolic patterns. Specifically, serotonin and cortisol are known to affect mood and emotional impulsivity. Normal neuroendocrine patterns are restored by the TM technique.

Recent research using SPECT technology has discovered severe metabolic abnormalities (functional lesions) in the brains of violent individuals. Since the TM program produces such marked improvements in brain biochemistry and electrical activity, we anticipate that these lesions will be normalized by the TM technique.

Therefore, the TM program is expected to restore normal neuroendocrine and brain metabolic function, thereby reversing the functional lesions observed in the brains of violent students. If these results are confirmed, the TM technique would provide an effective, much-needed approach to preventing school violence and youth crime.